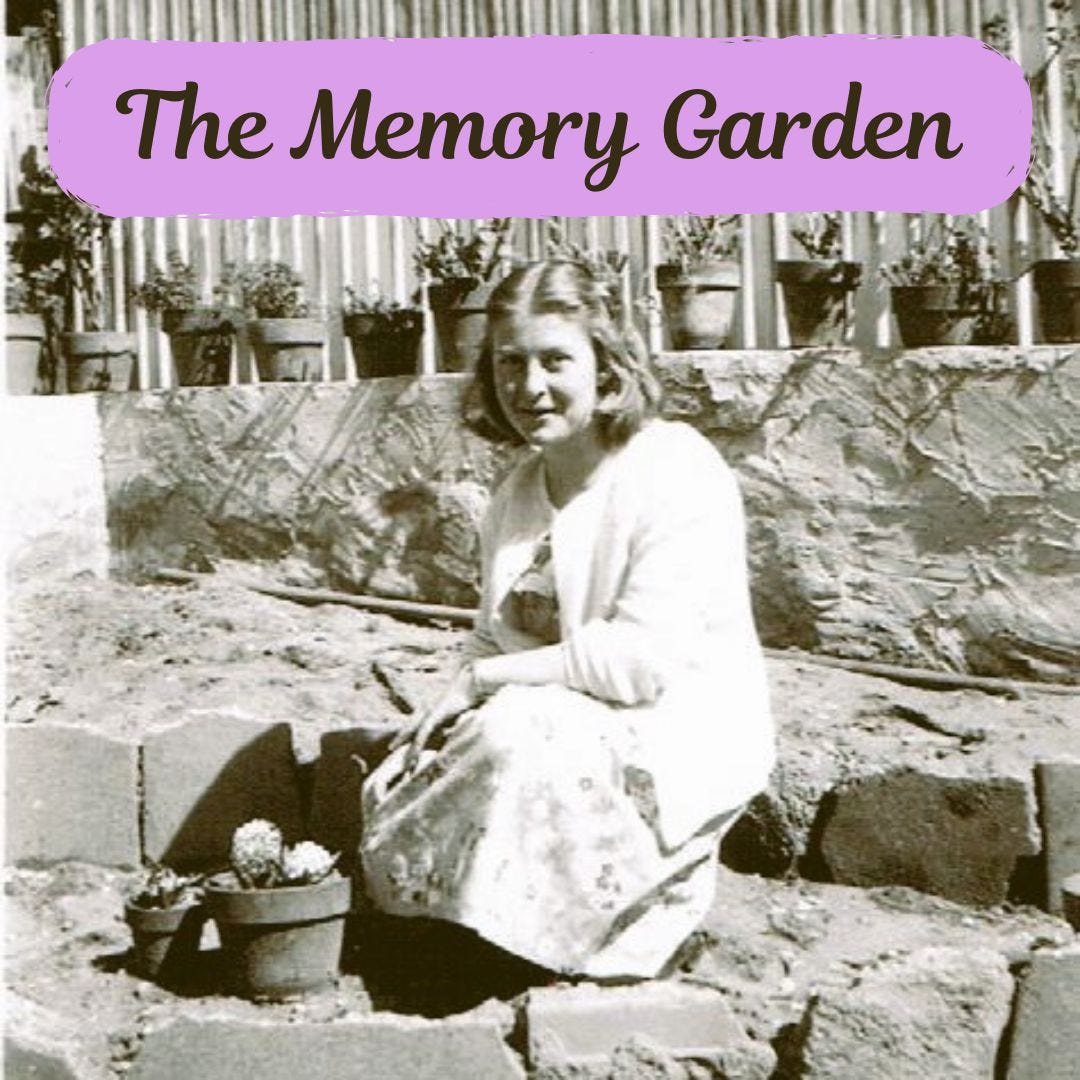

The Memory Garden: Remembering BH

A memory garden doesn't have to be about a person. Grieving the loss of a pet can be just as hard—or harder. And a garden can help.

The garden I’m making for my mother is not my first attempt at a memory garden. The first time I wanted to create a memory garden, the first time I even thought about such a concept, it was not for a person. It was for a pet, a 17-year-old, black-and-white shorthair cat named B.H. (short for Butthead). We were together from the time he was just a couple months old, a scrawny tuxedo-dressed kitten from a friend’s neighbor’s cat’s litter. He had a half-black/half-white snout and a funny, easygoing attitude and we bonded quickly.

I know there are people who write cats off as being indifferent and disconnected from the people around them, but those people never knew B.H. He was a terrific listener who took in my words as though he understood everything. One time, after a fight with a guy I was dating, I curled up on my bed and let the tears come. B.H. jumped up on the bed and leaned against me with a “tell me all about it” attitude that I’ll never forget.

Our bond grew even closer when I nearly lost him after he was hit by a car. Multiple surgeries followed, along with a vet bill that grew into the thousands but that I never hesitated to put on my credit card. For more than a month he had a splint on his leg and had to spend most of the day in a crate. While I had to leave him during the day to go to work, my mom would come to visit and take him out of the crate to stretch a bit and get some petting. At night I would take him out of the crate and lay on the sofa with B.H. stretched out across my chest, feeling our hearts beat against each other. In time he healed from those injuries and had a number of good, healthy years before he developed diabetes. Then came five years of twice-daily insulin shots that he withstood like a champ. Then his thyroid went haywire and within months, it was clear that he was failing fast. The day came when, with tears already streaming, I carried him into the vet’s office and we said goodbye. I held him through the last few breaths and then a little longer until I could bear to let go. I’m not sure what I was thinking I would do with his ashes when I asked for him to be cremated and the remains to be returned to me, but I knew I had to do it.

A couple weeks later I returned to the vet’s office to pick up a wooden box that held a plastic bag full of ashes. It sat on the buffet in the dining room for a few weeks, a painful reminder every time I saw it of the emptiness in the house. The truth is I was pretty wrecked. It’s one thing for the people in your life to recognize that you’ve just lost a pet and to sympathize. But when weeks and months pass and you’re still devastated, it can become something you don’t share for fear your grief won’t continue to be validated. In psychology it’s referred to as disenfranchised grief—"a mourning process not recognized socially after a loss.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lost in the Weeds to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.